What is phonological awareness? And why does it matter?

If you’ve never heard the term ‘phonological awareness’ before, it can sound pretty daunting. I certainly thought so when I first heard it and that was many years before I became a teacher.

But, though the words might sound a bit technical, the concept itself is actually quite simple and, if you have a baby or young child, it’s a fascinating thing to learn about.

Put simply, phonological awareness is an awareness of – and a sensitivity to – the sound structure of language. Huh? Let’s unpack that a bit.

Phonological awareness is about our ability to focus on three things:

- the sounds of speech, as distinct from the meaning of the words – on the intonation or rhythm of the speech;

- the fact that certain words rhyme;

- the separate sounds we hear (Konza, 2011);

If you think about those three things you might notice that they’re all about the way speech sounds. That’s because phonological awareness is a listening skill. This is really important and it’s something that a lot of people misunderstand. Phonological awareness is not about writing or spelling: it’s all about listening.

But why is phonological awareness important?

Phonological awareness is important because many, many research studies over the years have shown that it’s a critical skill for children to have before they start learning to read. In fact, phonological awareness in the pre-school years is the best predictor we have of children’s later reading and spelling success (Konza, 2011; Dunst, Meter & Hamby, 2011).

But there are many misconceptions around phonological awareness, even among teachers and academics. These misconceptions often lead parents and teachers to think that they should be explicitly teaching phonological awareness to children.

It’s important to know that most children don’t need to have phonological awareness actually taught to them. In children who are developing normally and whose home lives are not seriously disadvantaged or unsafe, phonological awareness will develop naturally and easily as a result of the activities and conversations children have with the caring adults in their lives.

Interestingly, children whose phonological skills are well-developed during the pre-school years often learn to read quickly and easily.

Sometimes they even learn to read before they start school. In fact, they often learn to read quite naturally, with little in the way of formal teaching.

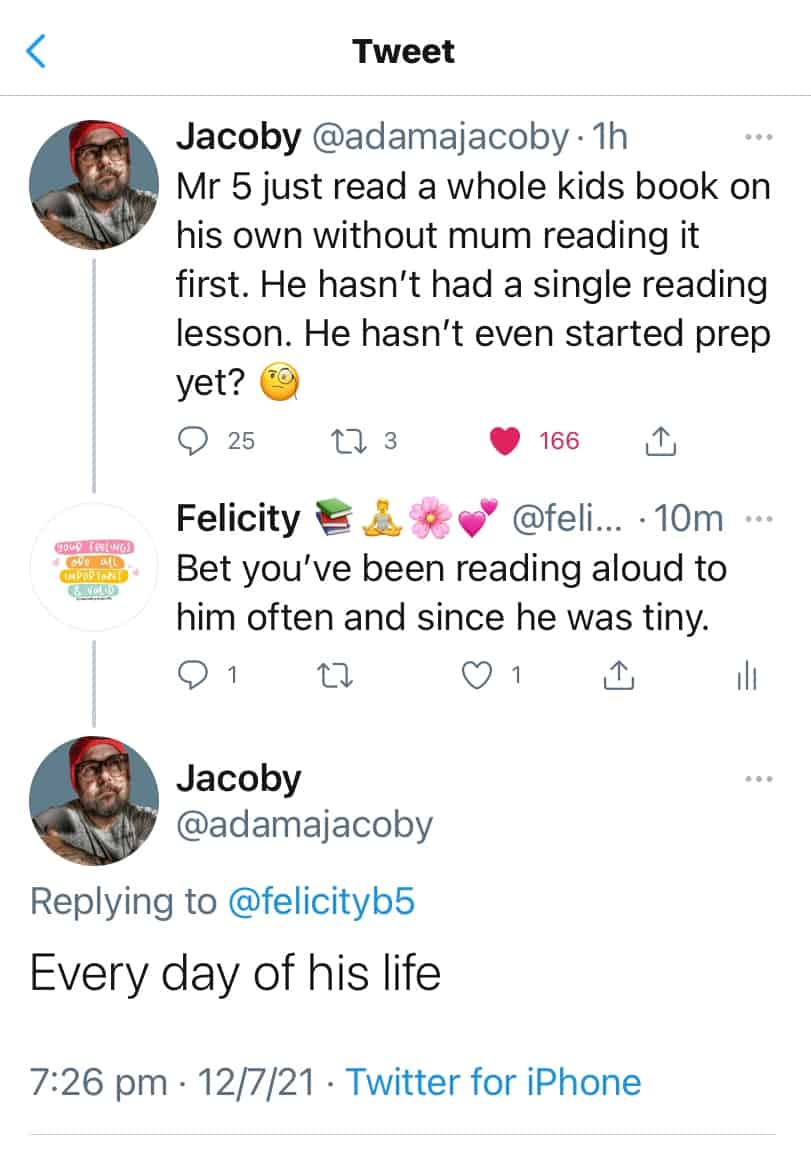

Sounds amazing, doesn’t it? Yet, I’ve seen this happen with quite a few children over the years, including my own three children and my five nephews. And, as you can see from the conversation I had on Twitter just a few days ago, it’s something that other parents experience too.

We’ll look into how this happens a little later but I think it’s good to look a bit more deeply into what phonological awareness is and what it is not, particularly when compared to phonemic awareness.

Phonological awareness vs phonemic awareness

Perhaps the most important thing to understand about phonological awareness is that it’s a listening skill. I mentioned this earlier but it’s really important to understand so it bears repeating.

Despite some common misconceptions, phonological awareness has nothing to do with reading, writing or spelling.

And phonological awareness is not the same thing as phonemic awareness.

The terms phonological awareness and phonemic awareness are sometimes used synonymously, even by teachers and in academic literature, so it’s not surprising that there is often confusion about what they actually mean. The two are related but they are not the same thing.

Phonological awareness is a broad listening skill which develops naturally in most children, starting from birth and continuing during the pre-school years.

Phonemic awareness, on the other hand, involves having the ability to identify and manipulate units of oral language, such as words and syllables.

Just to make things even more confusing, many pre-schoolers do, in fact, develop phonemic awareness as a result of being read to, sung to and as a result of playing rhyme games. But it’s important to understand that phonological awareness develops first and is a necessary precursor to the development of phonemic awareness.

Phonological awareness: ages and stages

When children are very young, you won’t actually be able to see any signs that they are becoming phonologically aware. The development is all going on in their brains and it’s completely invisible. But that doesn’t mean it’s not happening (Swingley, 2008).

If we want to understand the way phonological awareness develops, we need to start with the knowledge that babies are born with brains that are wired for the acquisition of oral language. In fact, we now know that their brains are tuning in to the sounds, rhythms and patterns of spoken language even before they’re born. Neuro-imaging studies on babies aged 4-6 months and 10-12 months have shown that a part of the brain called the left superior temporal gyrus is associated with phonetic processing while the left inferior frontal cortex is associated with the search and retrieval of information about meanings and syntactic and phonological patterning (Kovelman et al, 2011; Petitto et al, 2012).

All this brain activity means that, by the time a child says their first word at around 12 months of age, they may already know the phonological forms of hundreds of other words (Swingley, 2008).

How do I know my child is developing phonological awareness?

Phonological awareness usually becomes noticeable in the third year of a child’s life. This is when it becomes noticeable, however, it develops because of activities that the child has been exposed to from birth.

A three-year-old whose phonological awareness is developing might say something like: ‘Hey, cat-bat: they sound the same!’ To which you might reply ‘Hey, they do, don’t they? They both have an at sound in them. Cat-bat, bat-cat!’

As they get older, children will often demonstrate their awareness of the phonological forms of the words they hear by playing with them. So, for example, they might sing “Old MacDonald had a farm, fee, fie, fee, fie foe” or “Old MacDonald had a farm, lee, lie, lee, lie low” instead of the way the song is usually sung. A child who does this is demonstrating their sensitivity to – and awareness of – the rhythm and rhyme in the song.

Children sometimes progress from hearing an adult or another child manipulate sound units in a story or song and recognising this manipulation to being able to do it for themselves. Some children demonstrate their ability to do this without, as far as their parents know, having heard it done before. Either way, a child who can detect and manipulate the sounds in speech in this way is phonologically aware.

Phonological awareness activities for little ones

At the beginning of this post I said that, in most children, phonological awareness will develop naturally and easily as a result of the activities and conversations they have with the caring adults in their lives. We now have decades of research supporting this. There is also a great deal of research which shows that children who experience difficulties when they’re learning to read usually have poorly-developed phonological awareness (Kovelman et al, 2012).

So what are the activities parents and carers typically do with young children that support and stimulate the development of phonological awareness?

For four-year-olds, games like I Spy are fantastic, as are skipping rhymes. Music of all kinds and reading aloud continue to be super-important for this age group.

But I want to focus here on the phonological awareness activities parents and carers can do with babies from their earliest days which are fun, promote connection between carers and their little ones and will pay off in a big way later on.

These activities are:

- talking to babies;

- singing to them and playing music at home;

- reading aloud;

These simple activities all stimulate the sensitivity of our little one’s brains to the sounds in spoken language and, by doing this, support the development of phonological awareness. Engage in these activities with your child from their earliest days and your little one is likely to develop a playful love of language which will provide a strong foundation for learning to read later on.

When it comes to talking to and communicating with babies, Janet Lansbury has some very helpful ideas. I highly recommend reading her article What Your Baby Can’t Tell You.

When it comes to singing, download some songs by a band like The Wiggles and play them to your baby. Sing along and have a bit of a dance. Your baby will love it!

Nursery rhymes and poems are great stimulators of phonological awareness. Sing nursery rhymes (Google them if you can’t remember any) and buy a book of nursery rhymes to read aloud.

Nursery rhymes which incorporate finger play or actions are especially wonderful stimulators of phonological awareness. Think Incy Wincy Spider, This Little Piggy and Round and Round the Garden (Like a Teddy Bear).

But my favourite phonological awareness activity, hands-down, is reading aloud.

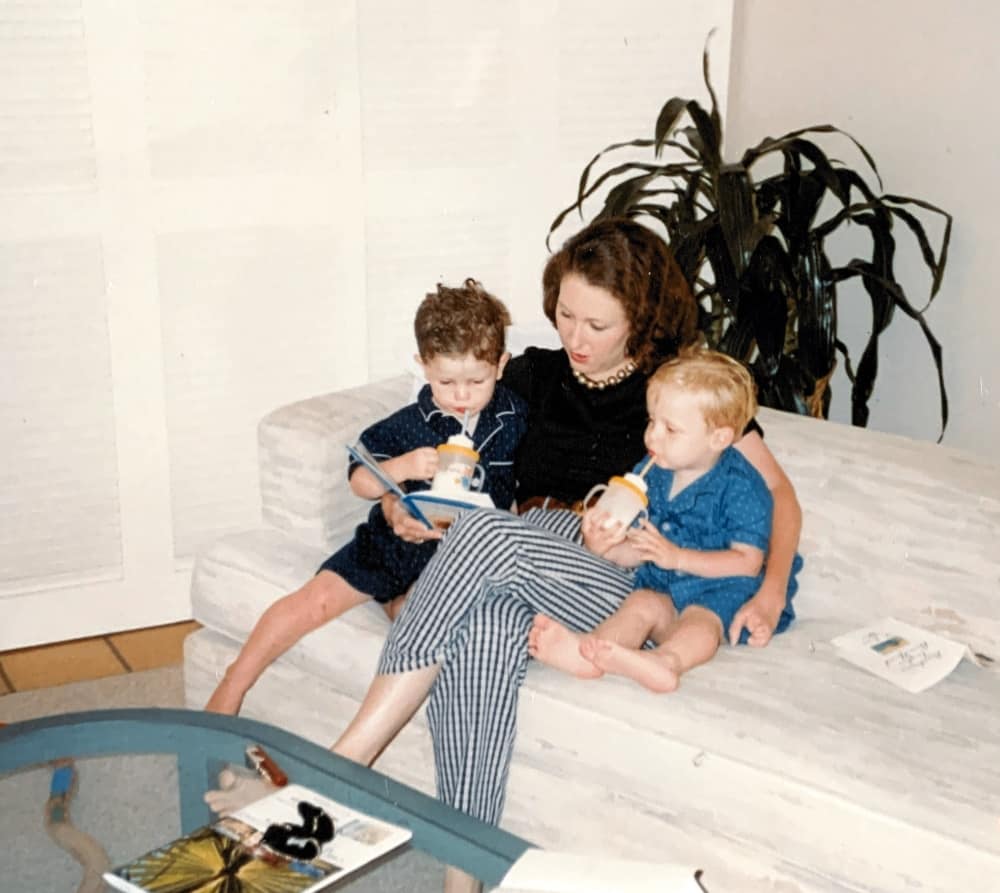

This is me, way back in November 1997, reading to my twin sons.

How reading aloud helps develop phonological awareness

Phonological awareness is one of the building blocks of learning to read. In fact it’s a crucial building block without which children struggle to learn to read. The other two building blocks are a rich vocabulary and a wide background knowledge.

And the very best way of helping your child develop all three of these skills is by reading to him often, starting as early as possible.

Poetry and rhyme in particular are great stimulators of phonological awareness.

Luckily, human beings seem to be naturally drawn to language which features rhyme, repetition and an interesting rhythm. You can see this quite clearly when you read a poem or rhyme to a child or when you sing a song. Even very young babies are usually entranced. That’s why so many books for young children are written in rhyming verse. It’s also why nursery rhymes have been popular for hundreds of years and why Dr Seuss books are so much fun to read with children.

When you read nursery rhymes, poems and rhyming books, your child hears rhythms, words and patterns of speech that she probably doesn’t hear in everyday conversations. This stimulates neural connections and helps your child’s brain tune in to the sounds of the language she will later learn to makes sense of in written form.

So, my suggestion is that parents aim to read aloud to their little ones every day from birth.

Read lots of different books, both favourites and new books.

Have fun with it. Make the silly voices and noises.

Visit the library every week and borrow loads of books.

Read aloud at bed-time and during the day.

Have board books on low shelves or in baskets so little ones can access them whenever they like.

Buy books for birthdays and as special treats.

What should you read?

Any good book will do. But, if you need a starting point, the following are wonderful books with which to begin.

Not all rhyming books are equal. Sometimes the rhymes sound very forced and the rhythm of the text seems all wrong. You’ll know what I mean the first time you read one of these books aloud.

The books I recommend below are wonderful to read aloud. All of them incorporate wonderful rhythms and fun rhymes and are beautiful additions to a child’s personal library.

Happy reading!

Books that stimulate the development of phonological awareness

These books all feature wonderful rhymes and rhythms and are fantastic fun to read aloud. I use these books in the classroom and regularly give them as gifts. Some are also included in the book gift baskets I sell on this website.

If you’re interested in buying one of these books or in learning more about them, the cover images include a link to the Book Depository website.

Full disclosure: these are affiliate links. if you choose to purchase a book after following the link, I will receive a small payment from the Book Depository, at no cost to you.

I’m Felicity - a parent to three young humans and a primary school teacher who loves books.

I’m passionate about helping parents discover the joy of reading to their little ones and I love helping you discover quality picture books to share with the babies and small humans in your lives.

I also create gift baskets and Little Book Gifts filled with the very best books for children from newborns to four-year-olds. You can check them out here.

SEARCH THE BLOG

SHOP OUR BOOK GIFT BASKETS

Over to you

Do you play rhyming games with your little one?

Have you noticed signs that your child’s phonological awareness skills are developing?

I’d love to hear what you think so drop me a line in the comments.

References

Clark, C. (2019, 13 June). The Ultimate Guide to Phonological Awareness and Pre-Reading Skills. Speech and Language Kids. Retrieved 10 July 2021: https://www.speechandlanguagekids.com/ultimate-guide-phonological-awareness-pre-reading-skills/

Dunst, C.J; Meter, D; Hamby, D. (2011). Relationship Between Young Children’s Nursery Rhyme Experiences and Knowledge and Phonological and Print-Related Abilities. Center for Early Literacy Learning, 4(1), 1-12.

Konza, D. (2011). Phonological Awareness. Research into practice, 1(1.2), 1-6.

Kovelman, I; Norton, E.S; Christodoulou, J.A; Gaab, N; Lieberman, D.A; Triantafyllou, C; Wolf, M; Whitfield-Gabrieli, S; Gabrieli, J.D.E. (2012). Brain Basis of Phonological Awareness for Spoken Language in Children and Its Disruption in Dyslexia. Cerebral Cortex, Volume 22(4), 754-764.

New South Wales Government. (2020, 26 June). Phonological Awareness. New South Wales Department of Education. Retrieved 9 July 2021: https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/curriculum/literacy-and-numeracy/teaching-and-learning-resources/literacy/effective-reading-in-the-early-years-of-school/phonological-awareness

Petitto, L.A; Berens, M.S; Kovelman, I; Dubins, M.H; Jasinska, K; & Shalinsky, M. (2012). The “Perceptual Wedge Hypothesis” as the basis for bilingual babies’ phonetic processing advantage: New insights from fNIRS brain imaging. Brain and Language, Vol 121(2), 130-143.

Reading Rockets. (2016, 14 April). Phonological and Phonemic Awareness. Retrieved 10 July 2021: https://www.readingrockets.org/helping/target/phonologicalphonemic

Swingley, D. (2008). The roots of the early vocabulary in infants’ learning from speech. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(5), 308–311. Retrieved 14 July 2021: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2879636/

Yopp, H.K. & Yopp, R.H. (2009). Phonological Awareness Is Child’s Play! Young Children, V64(1), 12-18.

0 Comments